Severe wounds are typically treated with full thickness skin grafts. Some new work by researchers from Michigan Tech and the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat Sen University in Guangzhou, China might provide a way to use a patient’s own stem cells to make split thickness skin grafts (STSG). If this technique pans out, it would eliminate the needs for donors and could work well for large or complicated injury sites.

This work made new engineered tissues were able to capitalize on the body’s natural healing power. Dr. Feng Zhao at Michigan Tech and her Chinese colleagues used specially engineered skin that was “prevascularized, which is to say that Zhao and other designed it so that it could grow its own veins, capillaries and lymphatic channels.

This innovation is a very important one because on of the main reasons grafted tissues or implanted fabricated tissues fail to integrate into the recipient’s body is that the grafted tissue lacks proper vascular support. This leads to a condition called graft ischemia. Therefore, getting the skin to form its own vasculature is vital for the success of STSG.

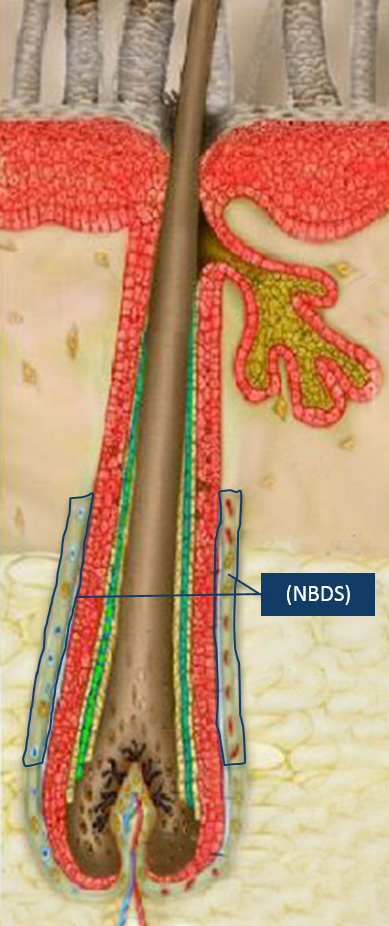

STSG is a rather versatile procedure that can be used under unfavorable conditions, as in the case of patients who have a wound that has been infected, or in cases where the graft site possess less vasculature, where the chances of a full thickness skin graft successfully integrating would be rather low. Unfortunately, STSGs are more fragile than full thickness skin grafts and can contract significantly during the healing process.

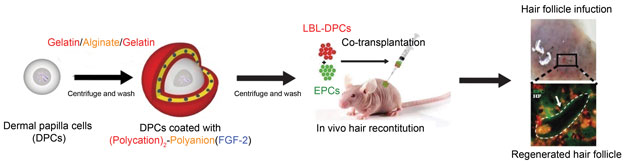

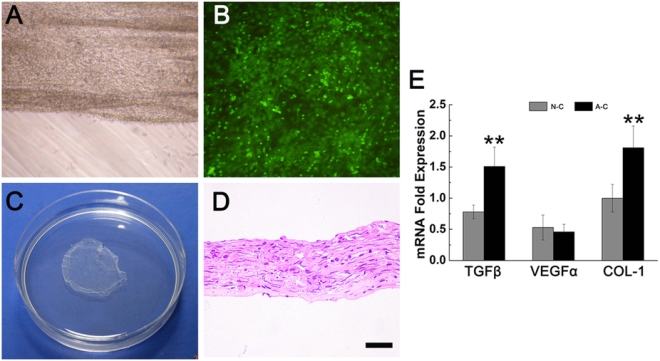

In order to solve the problem of graft contraction and poor vascularization, Zhao and others grew sheets of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and mixed in with those MSCs, human umbilical cord vascular endothelial cells or HUVECs. HUVECs readily form blood vessels when induced, and growing mesenchymal stem cells tend to synthesize the right cocktail of factors to induce HUVECs to form blood vessels. Therefore this type of skin is truly poised to form its own vasculature and is rightly designated as “prevascularized” tissue.

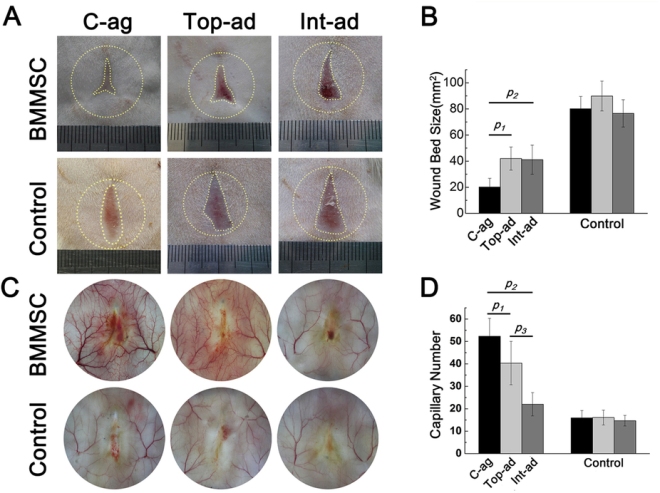

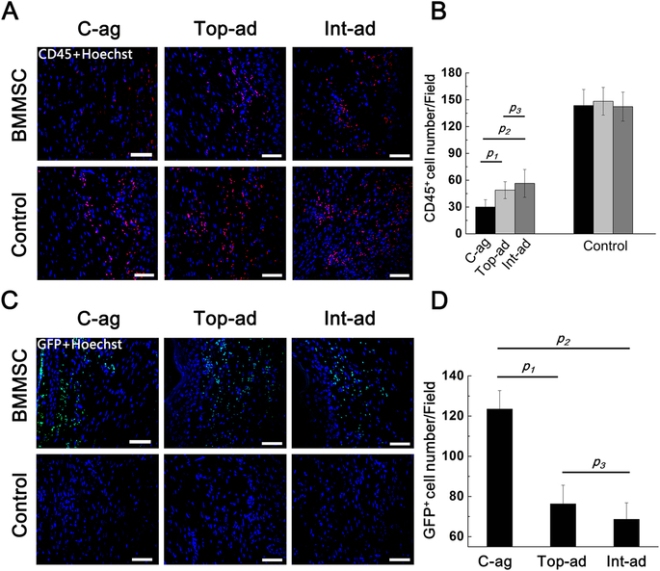

Zhao and others tested their MSC/HUVEC sheets on the tails of mice that had lost some of their skin because of burns. The prevascularized MSC/HUVEC sheets significantly outperformed MSC-only sheets when it came to repairing the skin of these laboratory mice.

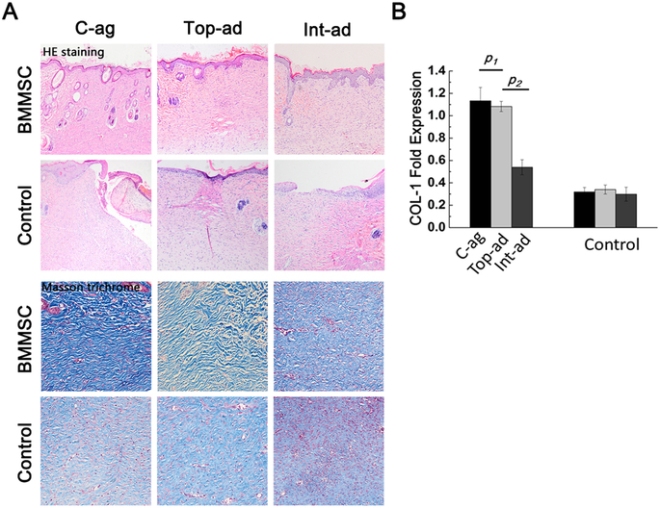

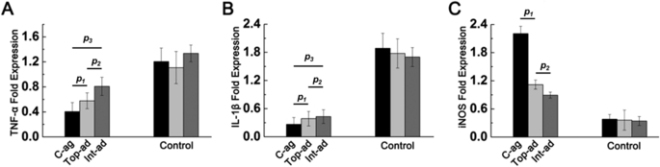

When implanted, the MSC/HUVEC sheets produced less contracted and puckered skin, lower amounts of inflammation, a thinner outer skin (epidermal) thickness along with more robust blood microcirculation in the skin tissue. And if that wasn’t enough, the MSC/HUVEC sheets also preserved skin-specific features like hair follicles and oil glands.

The success of the mixed MSC/HUVEC cell sheets was almost certainly due to the elevated levels of growth factors and small, signaling proteins called cytokines in the prevascularized stem cell sheets that stimulated significant healing in surrounding tissue. The greatest challenge regarding this method is that both STSG and the stem cell sheets are fragile and difficult to harvest.

An important next step in this research is to improve the mechanical properties of the cell sheets and devise new techniques to harvest these cells more easily.

According to Dr. Zhao: “The engineered stem cell sheet will overcome the limitation of current treatments for extensive and severe wounds, such as for acute burn injuries, and significantly improve the quality of life for patients suffering from burns.”

This paper can be found here: Lei Chen et al., “Pre-vascularization Enhances Therapeutic Effects of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Sheets in Full Thickness Skin Wound Re-pair,” Theranostics, October 2016 DOI: 10.7150/ thno.17031.