Mesoblast Limited has announced results from its Phase 2 clinical Trial that evaluated their Mesenchymal Precursor Cell (MPC) product, known as MPC-300-IV, in patients who suffer from diabetic kidney disease. In short, their cell product was shown to be both safe and effective. The results of their trial were published in the peer-reviewed journal EBioMedicine. Researchers from the University of Melbourne, Epworth Medical Centre and Monash Medical Centre in Australia participated in this study.

The paper describes a randomized, placebo-controlled, and dose-escalation study that administered to patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy either a single intravenous infusion of MPC-300-IV or a placebo.

All patients suffered from moderate to severe renal impairment (stage 3b-4 chronic kidney disease for those who are interested). All patients were taking standard pharmacological agents that are typically prescribed to patients with diabetic nephropathy. Such drugs include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (e.g., lisinopril, captopril, ramipril, enalapril, fosinopril, ect.) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (e.g., irbesartan, telmisartan, losartan, valsartan, candesartan, etc.). A total of 30 patients were randomized to receive either a single infusion of 150 million MPCs, or 300 million MPCs, or saline control in addition to maximal therapy.

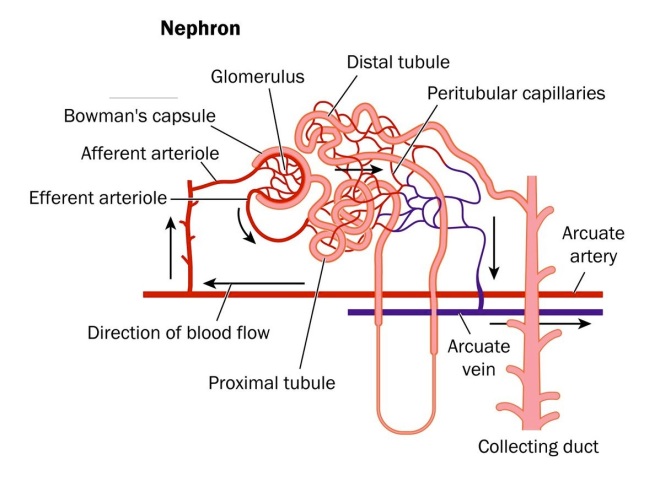

Since this was a phase 2 clinical trial, the objectives of the study were to evaluate the safety of this treatment and to examine the efficacy of MPC-300-IV treatment on renal function. For kidney function, a physiological parameter called the “glomerular filtration rate” or GFR is a crucial indicator of kidney health. The GFR essentially indicates how well the individual functional units within the kidney, known as “nephrons,” are working. The GFR indicates how well the blood is filtered by the kidneys, which is one way to measure remaining kidney function. The decline or change in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is thought to be an adequate indicator of kidney function, according to the 2012 joint workshop held by the United States Food and Drug Administration and the National Kidney Foundation.

Diabetic nephropathy is an important disease for global health, since it is the single leading cause of end-stage kidney disease. Diabetic nephropathy accounts for almost half of all end-stage kidney disease cases in the United States and over 40% of new patients entering dialysis treatment. For example, there are almost 2 million cases of moderate to severe diabetic nephropathy in 2013.

Diabetic nephropathy can even occur in patients whose diabetes is well controlled – those patients who manage to keep their blood glucose levels at a reasonable level. In the case of diabetic nephropathy, chronic infiltration of the kidneys by inflammatory monocytes that secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines causes endothelial dysfunction and fibrosis in the kidney.

Staging of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is based on GFR levels. GFR decline typically defines the progression to kidney failure (for example, stage 5, GFR<15ml/min/1.73m2). The current standard of care (renin-angiotensin system inhibition with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers) only delays the progression to kidney failure by 16-25%, which leaves a large residual risk for end-stage kidney disease. For patients with end-stage kidney disease, the only treatment option is renal replacement (dialysis or kidney transplantation), which incurs high medical costs and substantial disruptions to a normal lifestyle. Due to a severe shortage of kidneys, in 2012 approximately 92,000 persons in the United States died while on the transplant list. For those on dialysis, the mortality rate is high with an approximately 40% fatality rate within two years.

The main results of this clinical trial were that the safety profile for MPC-300-IV treatment was similar to placebo. There were no treatment-related adverse events. Secondly, patients who received a single MPC infusion at either dose had improved renal function compared to placebo, as defined by preservation or improvement in GFR 12 weeks after treatment. Third, the rate of decline in estimated GFR at 12 weeks was significantly reduced in those patients who received a single dose of 150 million MPCs relative to the placebo group (p=0.05). Finally, there was a trend toward more pronounced treatment effects relative to placebo in a pre-specified subgroup of patients whose GFRs were lower than 30 ml/min/1.73m2 at baseline (p=0.07). In other words, the worse the patients were at the start of the trial, the better they responded to the treatment.

The lead author of this publication, Dr David Packham, Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of Melbourne and Director of the Melbourne Renal Research Group, said: “The efficacy signal observed with respect to preservation or improvement in GFR is exciting, especially given that this trial was not powered to show statistical significance. Patients receiving a single infusion of MPC-300-IV showed no evidence of developing an immune response to the administered cells, suggesting that repeat administration is feasible and may in the longer term be able to halt or even reverse progressive chronic kidney disease. I hope that this very promising investigational therapy will be advanced to rigorous Phase 3 clinical trials to test this hypothesis as soon as possible.”

Patients who received s single IV infusion of MPC-300-IV cells showed no evidence of developing an immune response to the administered cells. This suggests that repeated administration of MPCs is feasible and might even have the ability to halt, or even reverse progressive chronic kidney disease.

Packham and his colleagues hope that this cell-based therapy can be advanced to a rigorous Phase 3 clinical trial to further test this treatment.